In the coming days we are invited to encounter the power of an ancient tradition that makes a particular period of time sacred: we call it ‘holy week’. It culminates in the final three days in the transcendence of time, the bursting of the eternal present into the human dimension of time and space.

If we can feel it as an invitation, we could experience hospitality in its fullest meaning. Today the ‘hospitality industry’ means pubs, restaurants and hotels and is an important part of the economy in the service sector. Spiritually and in traditional societies, however, hospitality is an experience of a mysterious relationship in which roles are reversed and oppositions are entwined.

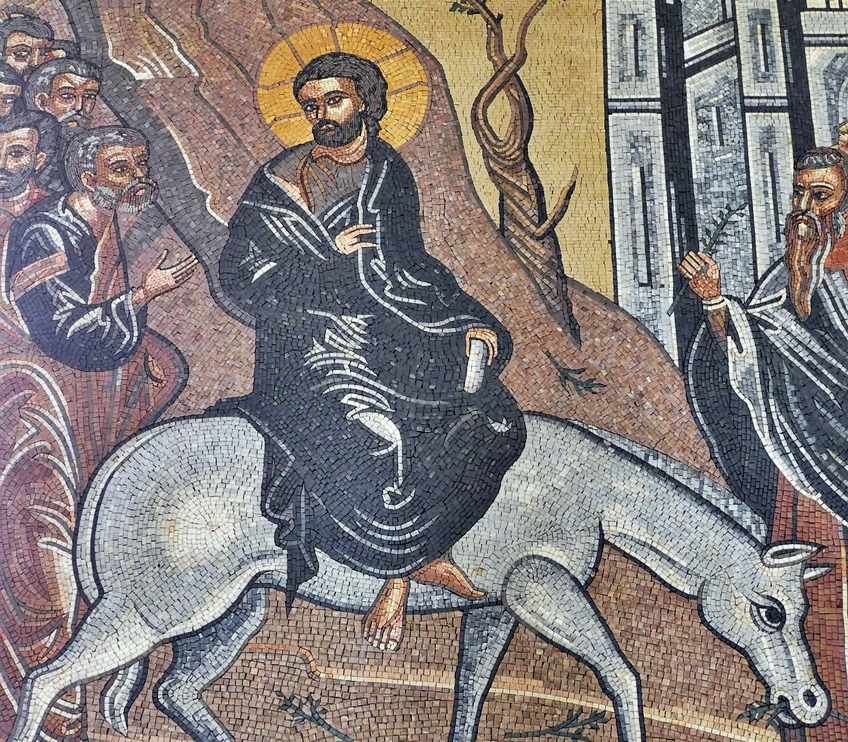

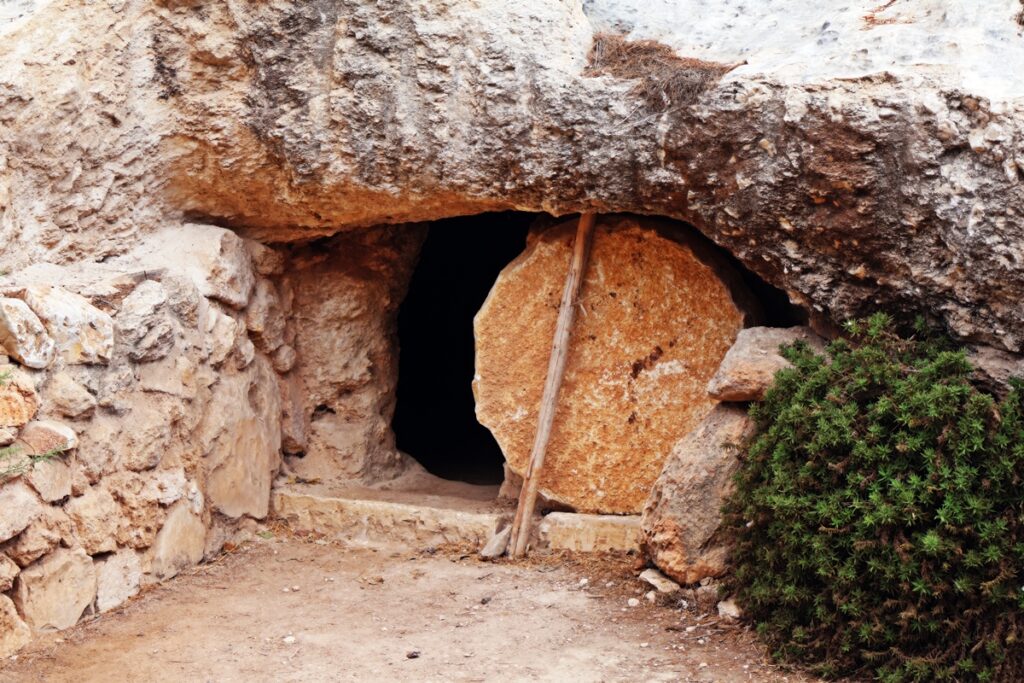

Today, Palm Sunday, remembers the triumphal welcome of Jesus into Jerusalem. The crowd of pilgrims who had come for the religious festival went wild and he seemed to be riding high in a way that a celebrity or a politician longs for. People wanted to see the man reputed to have raised the dead. Ironically, Jesus rode in not on a beautiful white horse but on a donkey. In a few days, the crowd had turned against him and were clamouring for his death as a blasphemer. That hospitality of Jerusalem proved shallow and false.

The root word for hospitality is the Latin hospes which oddly contains three meanings: guest, host and stranger. Stranger also hints at ‘enemy’ and links hospes also to the word ‘hostile’. Strangers are visitors from the foreign and the unknown. Maybe they are potential friends. But don’t trust them yet, even if they come bearing gifts. Prudence says treat them as friends, even as divine visitors. In some cultures, the welcoming host become responsible for the safety and well-being of the stranger whether they need a hotel or a hospital. In India the principle of Atithi Devo Bhava, the guest is God, must always be respected. In Christian communities the guest must be welcomed as if they were Christ himself and in a few countries this even applies to immigrants. The Qu’ran says that even prisoners of war should be treated like guests

Strangers pose possible dangers; and maybe the social custom of exaggerated hospitality is a way of protecting the host from them. But deeper than this fear is the vision of God present in in everyone. That insight arises from the simple and universal experience of human kinship. Some theories say that there is a hidden hostility in hospitality as it distances us from the stranger. But beyond theory, in the practice of gracious, courteous welcoming the projections of divinity or danger on the guest can be resolved. The Christ in me welcomes the Christ in you. Human relationship moves into a higher level, almost the highest level of nondualism. In this atmosphere, fear, division, conflict cannot survive. There is peace and unity.

If we see Holy Week as an invitation, then, we may soon find this peace even through the intense changes of mood and the tragic-transcendent conclusion of the following days. We will make a passover from a vision of life seen through the prism of fear to one of confidence and trust. I saw the almost full bright moon just now, walking out after meditation. She is both guest and host and a familiar stranger.

Both Passover and Easter festivals are controlled and reconciled by her. She is full-faced, innocent and lovely and you can bask in her cool healing light without any fear.

Today, the Annunciation, is the real feast of the incarnation, nine months before Christmas Day. It must be one of the most frequently imagined and represented events in human history: an angel appearing to a young girl probably between fourteen and nineteen. (Shakespeare’s Juliet was thirteen). The angel told her not to be afraid but that she was chosen to bear a child, whose name would be Jesus. Mary gave her assent and opened her will to that of God in a very simple formula: Here I am… What you have said, so be it. The conception happened in her surrender to her being ‘overshadowed’ by the Holy Spirit.

This story is of the greatest mythic simplicity which modern rationalistic minds find as difficult to understand as it does magic and any post-rational vision of reality. We need to ask ourselves if we would like to understand it. But when we hear it for the first time, we need only to be open to it, to listen without dismissing it as ‘just a fairy tale’, and to hear it again and again until a feeling of awe replaces our scepticism. Maybe for us the focal point is not imagining how beautiful the angel was but instead focus on Mary’s existential dilemma. And her swift transition from rational scepticism – ‘how can this be?’ – to the total personal surrender of ‘Here am I; I am the Lord’s servant; as you have spoken so be it.’ (Lk 1:26-38).

Paying attention to this is more respectful and effective than trying to deconstruct the words or imagine ‘what, if anything, actually happened’. Sacred texts in all traditions resolutely resist this sort of treatment and insist instead that we surrender to a way of unknowing if we are to understand. The tender, powerful beauty of the paintings of the Annunciation found in churches and galleries the world over, help us to trust the story as a channel of sacred truth without our yet understanding it.

We aren’t supposed to celebrate the Annunciation in Holy Week so there is another gospel which describes Mary of Bethany, her sister Martha and their brother Lazarus whom he raised from the dead, entertaining Jesus at an evening meal a week before his death. Mary, the symbol of contemplation opens a bottle of very expensive perfume, ‘oil of nard’. Nard was associated with a beautiful scent but also with its properties as a sedative and a medicinal herb. Mary anoints the feet of Jesus with the ointment; and he defends her gesture when Judas attacks her for wasting something valuable that could have been sold and given to the poor.

Both gospels defy exclusively rational understanding. But also both are like a key to opening the mind to the intelligence of the heart. This brings a widening of our tent, which is the enclosed space consciousness and our way of judging everything – until we discover, through beauty or love, in words or silence that we each have within us a capacity to see beyond the surface of things and trust the unknown depth. ‘We cannot create experience, we must undergo it.’

The plot thickens and quickens in John’s description of the Last Supper. Jesus is reclining at the dinner, surrounded by his close companions. He again feels deeply troubled, knowing he will be betrayed and tells them so. When he dips a piece of bread into the dish and hands it to Judas, ‘Satan enters Judas’ and, when Jesus tells him to do what he has to do, Judas leaves the table to go and tell the authorities where they can arrest Jesus later that night. None of the others understand what is happening.

What is happening? The shadow is emerging from the shadows and, if not yet visible to all, its influence is and will be felt by everyone. Although the gospels tend to demonise Judas as a traitor, Jesus, while knowing what he is doing, sees his betrayal in the large perspective. This global perspective is the fruit of a profound interior life which enables us, and him pre-eminently, to understand every action in terms of its ultimate effect. That Jesus sees this action in this perspective, personally painful as it is at this dark moment, is made clear by his comment that it triggers his own ‘glorification’.

Glory is a slippery word as it suggests something external, lustrous, dressed up, dripping in medals and jewels. The real meaning is much more about revealing the value of someone as they truly are. One literal translation suggests: to ‘ascribe weight by recognising real substance and value’. One cannot glorify oneself. One has to be recognised for who one truly is.

The radical paradox is that Judas’ betrayal is part of a process that reveals who Jesus truly is. Because of his profound interior life and clarity of self-knowledge – still evolving until his last breath – Jesus understands this. This self-awareness explains the equanimity and peace that we see in him throughout his coming Passion.

As always, this understanding of the scripture flashes us back a message – ‘and what about you, o reader, what about your interior life?’

As the mystical understanding of Jesus developed in the early church, awareness grew in the whole Christian community about the importance of the interior life in each individual. The words of Jesus revealing the power of the inner truth of his self-knowledge became better understood and recognised. With this came the insight that to follow him means to grow in the interior life, to expand the perspectives of our understanding, to deepen and clarify our consciousness.

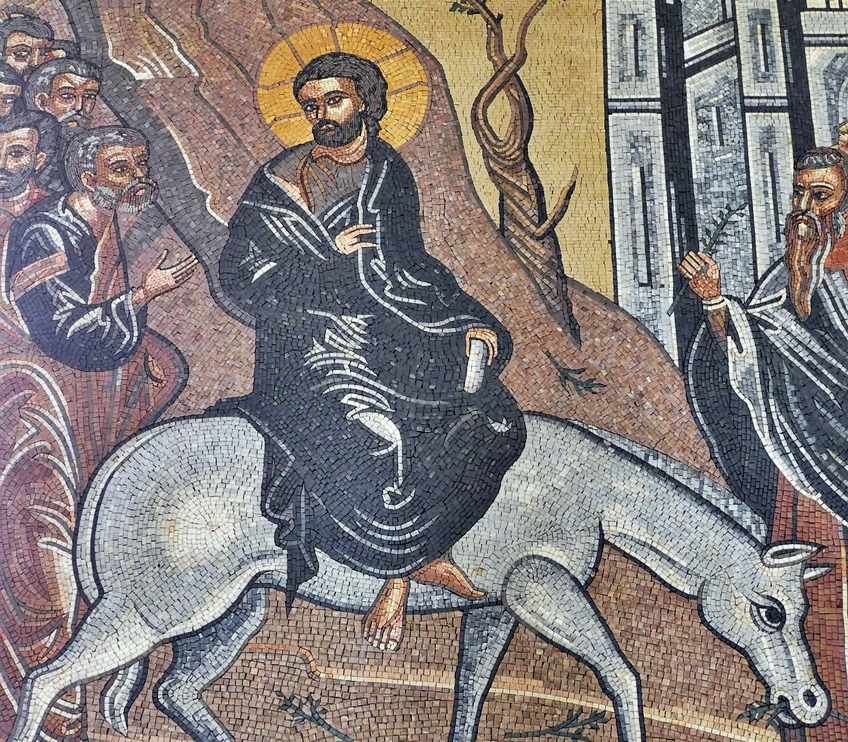

This becomes explicit not just in the lecture rooms of the early Christians but primarily in the cells and hermitages of the monastic movement spreading rapidly in the desert. The basic understanding there was to develop interiority through deep attention to oneself, while avoiding the obvious pitfall of increasing rather than transcending our egoism. Then as now the danger of contemplative life is narcissism. To avoid it we need guides, companions, discipline in practice and a robust sense of humour.

Aren’t these two of the kind of experiences which we can’t create or control but only undergo and, to some extent, perhaps, share with others whom we trust? By sharing I don’t mean we can really describe or explain them because, as soon as we try, we sound nonsensical. If you are going to speak meaningful nonsense to someone you first need to feel trust.

First, the sense of sheer wonder that the world exists and that we exist as part of it. It is wonder without the judgement that ‘I’m happy’ or ‘I am discontented’. Wonder does not even require we settle the question of why the world exists? Wonder is a pure response to what anything is in itself, without even comparing it with anything else. Childlike wonder, humbling and delightful at the same time.

Second is the conviction that everything will be OK, in the fullest sense of those two letters. Mother Julian clearly possessed it, when she said: ‘all will be well and every kind of thing will be well’. It can fill us even when appearances make us feel the exact opposite, that everything is doomed and will collapse into non-existence by tea-time.

When we play host to these experiences, we ‘feel better’ even though they don’t solve all our problems – except perhaps the big double-headed problem of despair and boredom. What makes us feel better, then, when we feel in a state of wonder and fundamental security? Whatever it is, it is like meditation – which doesn’t change external events in a magical way and at first doesn’t even numb us against the pain of uncertainty. But meditation is a quiet, gentle way of preparing us to welcome these two experiences and helping them become permanent guests and eventually co-residents in the house of being.

I trust you will forgive me if this sounds nonsense. When we think or speak about anything on the other side of language and thought we make nonsense. To make sense of it why not call the state of wonder and radical confidence ‘faith’. Belief, with which we usually confuse it, is influenced by faith; but faith itself is independent of belief. Faith is spiritual knowledge.

As we enter into the meaning of Holy Week and allow its central story to read us and show us our place in it, faith is the path we are following. We test and reset our beliefs against the experience of faith. Hiding behind faith is hope and secreted in hope is love. Like the eternal engine of God, these three are one.

From the first century of the Christian era St Ignatius of Antioch reminds every seeker today that

the beginning is faith, the end is love and the union of the two is God. Everything else follows on these and lead to perfect goodness.

The idea of sacrifice leads us deep into how human beings live and understand life. We are prepared to renounce ourselves for the sake of our children, country, cause or friends we love. Parenthood is a sacrificial offering extending over many years. But also the idea of sacrifice has shaped religious consciousness since the dawn of time. When we entered the magical way of seeing the world sacrifice became a way of influencing the higher forces and gods that controlled us. We give you this so that you will be gracious and give us what we ask.

Deeper than magic, however, sacrifice could also illuminate the deep, loving involvement of humanity and the divine powers. In Aztec mythology, Nanativatzin was the humblest of the gods. So that he could continue to shine as the life-giving sun over the earth and its inhabitants he sacrificed himself in fire.

The Eucharist fulfils this primordial religious practice and overcomes the dualism separating God and humanity and the community itself. We don’t need magic anymore and there is no fear in celebrating the great oneness. Yet, there is a great diversity in how different traditions express just how the sharing of bread and wine fuses Jesus’ offering of himself both at the Last Supper and on the Cross. None of the different styles of Eucharist with their different theologies would be celebrated, however, if it were not that doing so raised our consciousnesses of his real presence – in the fellowship of believers, in the Word and also in the ordinariness of bread and wine. In her poetic account of her mystical experience of Christ, Simone Weil included a down-to-earth eucharistic moment.

That bread truly had the taste of bread… the wine tasted of the sun and of the soil on which that city was built.

Although the Eucharist has been horribly politicised and exploited throughout history it survives in its original and spiritual freedom as a symbol of both the essential unity and the wild diversity of Christian faith. It will survive the present deconstruction of the institutions and will be re-discovered as a sacrament of the mystical Body expressing and nurturing the contemplative life.

From childhood, the gospel descriptions of the last days and hours of Jesus’ life have gripped and fascinated me as something of supreme importance and meaning. Each part of the story is part of me. As we prepare for good Friday here at Bonnevaux after a rather fun Holy Thursday celebration, it could feel like ‘well this is life’: celebration today, bad news or worse tomorrow. Does it have any meaning, this cycle of joy and misery? Or is it just about accepting what we have to? But, asking that feels like missing the point, looking for explanations where none exist.

When you can’t explain something, give statistics. Overall, the gospels give a disproportionate amount of space to describing these last hours : 30% of all the gospel texts about this 33-year-old man is given to his last two or three days. John, the deepest gospel gives 43% and 40% from Mark, the shortest and first gospel. It feels better to have measured it even though the gospels still do not give any explanation of its meaning. Why is his death so important? Why couldn’t more of his earlier life, his personality, especially his teachings, have been included and the last moments reduced?

So, although the Good Friday is so significant to me I cannot easily say why. What I was taught originally – Jesus died for us because of original sin – is the classic ‘atonement theory’. Even when I was young it didn’t convince me although I didn’t argue with it. Wittgenstein, who believed the Resurrection could only be understood by love, said that ‘whereof we cannot speak we must remain silent.’

I’ll squeeze in a few more words to explain why this response of silence can be applied to the attempt to explain the death of Jesus. First, that the details are unforgettably powerful – the last words (Father forgive them for they know not what they do; Today you will be with be in paradise (to the thief crucified beside him); I am thirsty; It is accomplished.) The scenes like carrying the cross, the soldiers casting lots, the triple denial of Peter. They all seem highly significant, inevitable, predictable, fulfilling destiny but unexplained and inexplicable.

One explanation is that the description is not just an historical narrative but a collective memory filtered through the present experience of the Risen Jesus. It is as if Jesus is telling the story himself: not to give explanations but to draw us closer to himself by our free choice.

Why tell the story at all if he had not risen?

In the Good Friday liturgy – like a global wake repeated annually – there is a reading of the Passion that stops at his burial. But the stunningly eloquent explanation is the Veneration of the Cross. People are invited to come up in silence – if they wish – and kneel before, or kiss, or simply touch the wood of the cross in silence.

When I do, I feel – perhaps like all who come forward – as if it is something definitive and authentic and I don’t need to explain it. We don’t have to justify what we love. More important than an explanation is a real encounter with a real person in a new kind of reality.

For some time death remains very hypothetical in the human panorama of life. After the brief immortality of youth, and with our first experience of losing someone we love, death seems an increasing possibility. Even when we have the inexplicable grace of accompanying someone we love to the point where ‘it is accomplished’ and they breathe their last as we hold their hand, the actual moment falls like the blade of a guillotine. As on Holy Saturday, there is a great silence, absence and bottomless emptiness.

The way a person dies can expand the portals through which the grace of death – confronting us with the barest face of truth – sweeps over us. As they hang on their cross waiting, they may be peaceful, confident, accepting and even conspicuously full of wonder at what they are seeing and being summoned to and welcomed by. We may not see it exactly as they do but we see something of it by seeing that they see it. For a moment, because of our irritating ego, we may even feel left out and forgotten as they are irresistibly drawn into what they are seeing. When they take their last breath, this shared vision appears to end, like the falling of a stage curtain at the end of a performance. We are left alone with our memory, in an ever- depleted world, as they pass beyond all the ways we have grown used to recognising them.

No more powerful words have ever been written that communicate this wonder, peace with pain and searing grief than those we heard yesterday. We see what they saw of what he was seeing through a memory passed on by those who were there and suffered changed by what they saw, but could not explain. Unlike most memories, however, it did not start to weaken from the day after and eventually fail and enter the great forgetfulness that consumes everything. The hand we are holding begins to lose its human warmth, still precious but no longer belonging to the person we loved and lost.

As she wept, she peered into the tomb.. ‘they have taken my Lord away and I do not know where they have put him’.

Holy Saturday is a state of mind: a neutral zone between what we know and do not know. It is too full of emptiness and the absence is too present and the silence is deafening.

We should not imagine anything. It is a day to make meditation the priority.