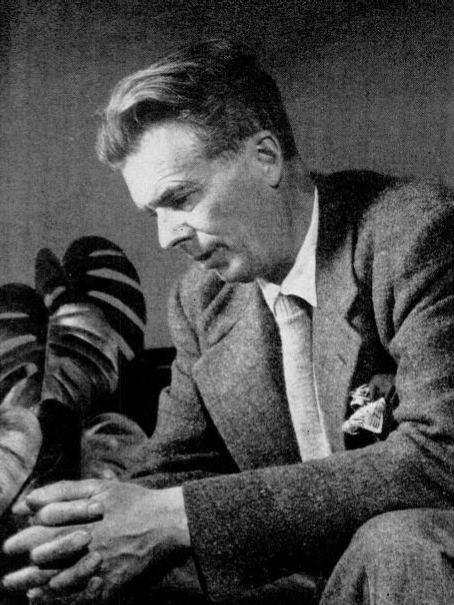

Aldous Huxley, 1894-1963, English writer and philosopher, was described by a contemporary as “a man of enormous intellect and gentle objectivity… one of the most hugely civilised human beings I have met”. Huxley is best known for the dystopian vision of his early novel, Brave New World, but this represents just one aspect of his wide-ranging interests. He became interested in philosophical mysticism, which he explored in The Perennial Philosophy, which looked at the commonalities between western and eastern mysticism. Further, he embraced modern science as well as the wisdom traditions.

For the last 24 years of his life, he had extensive involvement in the Vedanta Society of Southern California whose leader Swami Prabhavananda taught him meditation. During the years of the Second World War he moved to a small house in the Californian desert devoting himself to a life of contemplation. He remained an agnostic and found it difficult to fully embrace any form of institutionalised religion. He had deep apprehensions for the future of the developed world and his response was that of a contemplative: “we must learn how to be mentally silent, to cultivate the art of pure receptivity… we must learn to condition ourselves, to be able to cut holes in the fence of verbalised symbols which hems us in”.

I suspect he would have been very much at home in Fr. Laurence’s teaching on metanoia. If he was alive today I could imagine him lecturing at Bonnevaux.

During his time in the desert he wrote and published an extraordinary book: Grey Eminence, a biography of a man born in 1577 as Francois Leclerc du Tremblay. Francois became a Franciscan friar, and for the rest of his life he was known simply as Fr. Joseph of Paris. He became foreign minister of France in all but name, serving Cardinal Richelieu who was for many years the chief minister of France. Yet at the same time he devoted hours each day to contemplation (though not meditation as we have been taught it).The reason why Huxley got interested in writing his biography was this extraordinary combination of being a mystic with being a politician – and a politician moreover deeply involved in fomenting and prolonging the appalling horrors of the Thirty Years War – because that war was deemed to be in France’s interests.

There is one chapter in the strange biography of a strange man which I found fascinating and relevant to our meditation practice. The chapter describes the religious background to Fr. Joseph, and especially the contemplative spirituality of the time. Which leads Huxley to express strong opinions on the question of why the meditation tradition – on which of course our community is based – almost disappeared from western Christianity during the 17th century. But more of that later.

Huxley describes the development of the Christian tradition of contemplative prayer. He begins with the desert fathers and mothers, referencing Cassian whom he had obviously read, and moving onto Dionysius the Areopagite, the Cloud of Unknowing and other mediaeval mystics. He regards Dionysius as notably influential. The unknown Syrian monk who called himself by this name lived in the 5th century. Huxley devotes several pages to a summary of the teaching of the Cloud of Unknowing. He sees the Cloud as solidly in the Dionysian tradition. He includes incidentally a wonderful section on the difficulties posed by our mind’s absorption with trivial distractions.

Joseph however was influenced by the teaching of two religious of his time: the Englishman Benet of Canfield and the Frenchman Pierre de Berulle. They departed from traditional mysticism by insisting that “even the most advanced contemplatives should persist in “the practice of the passion”. In other words that they should meditate upon the sufferings of Christ “even when they had reached the stage at which it was possible for them to unite their souls with the godhead in an act of simple regard”. Huxley notes that the Dionysian mystics, whose religion was primarily experiential, had always maintained to the contrary. They had insisted that all ideas and images be put aside.

Huxley writes “the effect of Berulle’s [and Benet’s] … revolution was profound … and mainly disastrous. From the end of the 17th century to the end of the 19th mysticism practically disappeared out of the Catholic Church. … the causes are many and complex… there can be no doubt, however, that among these causes the Berullian revolution must take an important place. By substituting Christ and the virgin for the undifferentiated Godhead of the earlier mystics, Berulle positively guaranteed that none who followed his devotional practices should ever accede to the higher states of union or enlightenment. Contemplation of persons and their qualities entails a great deal of analytic thinking and an incessant use of the imagination. But analytic thinking and imagination are precisely the things which prevent the soul from attaining enlightenment. On this point all the great mystical writers, Christian and oriental, are unanimous and emphatic.” [My italics]

Grey Eminence is a strange book about a strange man living in very different times. But I did find the chapter on the spirituality of the 17th century fascinating. In offering introductory courses I have often talked about the origins of our tradition and its continuation into mediaeval times. Huxley ‘s book sheds some new light for me on why it largely disappeared in Western Christianity until its 20th century resurgence through luminaries such as Thomas Merton, Bede Griffiths, Thomas Keating and the other Spencer Abbey Cistercians, and of course, John Main.

Roger Layet.