Lent Reflections 2024

These daily reflections by Laurence Freeman, a Benedictine monk and Director of The World Community for Christian Meditation, are to help those following them make a better Lent. This is a set time and preparation for Easter, during which special attention is given to prayer, extra generosity to others and self-control. It is customary to give something up, or restrain your use of something but also to do something additional that will benefit you spiritually and simplify you. Running through these readings will be an encouragement to start to make meditation a daily practice or, if it already is, then to deepen it by preparing for the times of meditation more carefully. The morning and evening meditations then become the true spiritual centre of your day. Here is the tradition, a very simple way of meditation, that we teach:

Sit down, Sit still with your back straight. Close your eyes lightly. Breathe normally. Silently, interiorly begin to repeat a single word, or mantra. We recommend the ancient prayer phrase ‘maranatha’. It is Aramaic (the language of Jesus) for ‘Come Lord’, but do not think of its meaning. The purpose of the mantra is to lay aside all thoughts, good, bad, indifferent together with images, plans, memories and fantasies. Say the word as four equal syllables: ma ra na tha. Listen to it as you repeat it and keep returning to it when you become distracted. Meditate for about twenty minutes each morning and evening. Meditating with others, as in a weekly group, is very helpful to developing this practice as part of your daily life. Visit the community’s website for further help and inspiration: UK wccm.uk and International wccm.org

Happy Easter. And finally, we can say Alleuia again! One word says it all.

St John looked into the empty tomb and let Peter, his companion whom he had outrun to get there, go in first. Peter, the good but less subtle part of us. Then John, the lover in us, went in and ‘he saw and he believed’.

As I have been writing these reflections during Lent I have had an invisible companion, no doubt part of myself, who is not merely a non-believer but who does not just ‘believe’ either. This is an important part of ourselves to befriend and learn from because its questioning curiosity gives space for faith to grow and teach us things we never dreamed of before. We become enthusiastically inauthentic if we just jump up and down saying we ‘believe’. Anyway, the word we translate as ‘believe’ has much more content and outreach of meaning – to have faith in, to be persuaded, to trust. The English word ‘believe’ grows from the word ‘love’.

Something bursts today in humanity’s journey into consciousness, long imagined and much hoped-for. It is not like the working out of a solution to a maths problem or even like finishing a work we have been long engaged on. It is more like the bursting of a seed or the opening of a flower. It can best be recognised if we allow it, moment by moment, to persuade us that it understands us.

‘He comes to us hidden and salvation consists in our recognising him,’ Simone Weil said.

It is like seeing what makes a joke funny or why a pun can both please and irritate us. We don’t have to try too hard, just wait for the penny to drop. Today is just the beginning and if the beginning is so good imagine what the rest will be like.

I hope these Lent Reflections have been of some service for you during our long trek. I would like to thank the great team, led by Leonardo, who got them distributed and very specially the translators who patiently (I think) put up with some last-minute deliveries and for their very generous gift of time and wonderful talent.

One word says it all.

Happy Easter!

In the coming days we are invited to encounter the power of an ancient tradition that makes a particular period of time sacred: we call it ‘holy week’. It culminates in the final three days in the transcendence of time, the bursting of the eternal present into the human dimension of time and space.

If we can feel it as an invitation, we could experience hospitality in its fullest meaning. Today the ‘hospitality industry’ means pubs, restaurants and hotels and is an important part of the economy in the service sector. Spiritually and in traditional societies, however, hospitality is an experience of a mysterious relationship in which roles are reversed and oppositions are entwined.

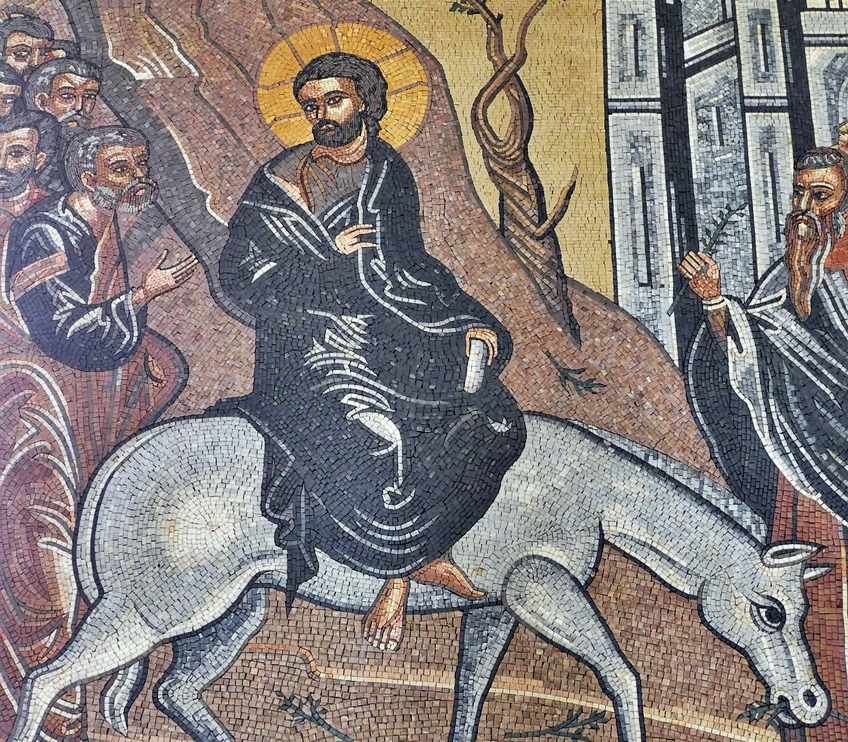

Today, Palm Sunday, remembers the triumphal welcome of Jesus into Jerusalem. The crowd of pilgrims who had come for the religious festival went wild and he seemed to be riding high in a way that a celebrity or a politician longs for. People wanted to see the man reputed to have raised the dead. Ironically, Jesus rode in not on a beautiful white horse but on a donkey. In a few days, the crowd had turned against him and were clamouring for his death as a blasphemer. That hospitality of Jerusalem proved shallow and false.

The root word for hospitality is the Latin hospes which oddly contains three meanings: guest, host and stranger. Stranger also hints at ‘enemy’ and links hospes also to the word ‘hostile’. Strangers are visitors from the foreign and the unknown. Maybe they are potential friends. But don’t trust them yet, even if they come bearing gifts. Prudence says treat them as friends, even as divine visitors. In some cultures, the welcoming host become responsible for the safety and well-being of the stranger whether they need a hotel or a hospital. In India the principle of Atithi Devo Bhava, the guest is God, must always be respected. In Christian communities the guest must be welcomed as if they were Christ himself and in a few countries this even applies to immigrants. The Qu’ran says that even prisoners of war should be treated like guests

Strangers pose possible dangers; and maybe the social custom of exaggerated hospitality is a way of protecting the host from them. But deeper than this fear is the vision of God present in in everyone. That insight arises from the simple and universal experience of human kinship. Some theories say that there is a hidden hostility in hospitality as it distances us from the stranger. But beyond theory, in the practice of gracious, courteous welcoming the projections of divinity or danger on the guest can be resolved. The Christ in me welcomes the Christ in you. Human relationship moves into a higher level, almost the highest level of nondualism. In this atmosphere, fear, division, conflict cannot survive. There is peace and unity.

If we see Holy Week as an invitation, then, we may soon find this peace even through the intense changes of mood and the tragic-transcendent conclusion of the following days. We will make a passover from a vision of life seen through the prism of fear to one of confidence and trust. I saw the almost full bright moon just now, walking out after meditation. She is both guest and host and a familiar stranger.

Both Passover and Easter festivals are controlled and reconciled by her. She is full-faced, innocent and lovely and you can bask in her cool healing light without any fear.

Today, the Annunciation, is the real feast of the incarnation, nine months before Christmas Day. It must be one of the most frequently imagined and represented events in human history: an angel appearing to a young girl probably between fourteen and nineteen. (Shakespeare’s Juliet was thirteen). The angel told her not to be afraid but that she was chosen to bear a child, whose name would be Jesus. Mary gave her assent and opened her will to that of God in a very simple formula: Here I am… What you have said, so be it. The conception happened in her surrender to her being ‘overshadowed’ by the Holy Spirit.

This story is of the greatest mythic simplicity which modern rationalistic minds find as difficult to understand as it does magic and any post-rational vision of reality. We need to ask ourselves if we would like to understand it. But when we hear it for the first time, we need only to be open to it, to listen without dismissing it as ‘just a fairy tale’, and to hear it again and again until a feeling of awe replaces our scepticism. Maybe for us the focal point is not imagining how beautiful the angel was but instead focus on Mary’s existential dilemma. And her swift transition from rational scepticism – ‘how can this be?’ – to the total personal surrender of ‘Here am I; I am the Lord’s servant; as you have spoken so be it.’ (Lk 1:26-38).

Paying attention to this is more respectful and effective than trying to deconstruct the words or imagine ‘what, if anything, actually happened’. Sacred texts in all traditions resolutely resist this sort of treatment and insist instead that we surrender to a way of unknowing if we are to understand. The tender, powerful beauty of the paintings of the Annunciation found in churches and galleries the world over, help us to trust the story as a channel of sacred truth without our yet understanding it.

We aren’t supposed to celebrate the Annunciation in Holy Week so there is another gospel which describes Mary of Bethany, her sister Martha and their brother Lazarus whom he raised from the dead, entertaining Jesus at an evening meal a week before his death. Mary, the symbol of contemplation opens a bottle of very expensive perfume, ‘oil of nard’. Nard was associated with a beautiful scent but also with its properties as a sedative and a medicinal herb. Mary anoints the feet of Jesus with the ointment; and he defends her gesture when Judas attacks her for wasting something valuable that could have been sold and given to the poor.

Both gospels defy exclusively rational understanding. But also both are like a key to opening the mind to the intelligence of the heart. This brings a widening of our tent, which is the enclosed space consciousness and our way of judging everything – until we discover, through beauty or love, in words or silence that we each have within us a capacity to see beyond the surface of things and trust the unknown depth. ‘We cannot create experience, we must undergo it.’

The plot thickens and quickens in John’s description of the Last Supper. Jesus is reclining at the dinner, surrounded by his close companions. He again feels deeply troubled, knowing he will be betrayed and tells them so. When he dips a piece of bread into the dish and hands it to Judas, ‘Satan enters Judas’ and, when Jesus tells him to do what he has to do, Judas leaves the table to go and tell the authorities where they can arrest Jesus later that night. None of the others understand what is happening.

What is happening? The shadow is emerging from the shadows and, if not yet visible to all, its influence is and will be felt by everyone. Although the gospels tend to demonise Judas as a traitor, Jesus, while knowing what he is doing, sees his betrayal in the large perspective. This global perspective is the fruit of a profound interior life which enables us, and him pre-eminently, to understand every action in terms of its ultimate effect. That Jesus sees this action in this perspective, personally painful as it is at this dark moment, is made clear by his comment that it triggers his own ‘glorification’.

Glory is a slippery word as it suggests something external, lustrous, dressed up, dripping in medals and jewels. The real meaning is much more about revealing the value of someone as they truly are. One literal translation suggests: to ‘ascribe weight by recognising real substance and value’. One cannot glorify oneself. One has to be recognised for who one truly is.

The radical paradox is that Judas’ betrayal is part of a process that reveals who Jesus truly is. Because of his profound interior life and clarity of self-knowledge – still evolving until his last breath – Jesus understands this. This self-awareness explains the equanimity and peace that we see in him throughout his coming Passion.

As always, this understanding of the scripture flashes us back a message – ‘and what about you, o reader, what about your interior life?’

As the mystical understanding of Jesus developed in the early church, awareness grew in the whole Christian community about the importance of the interior life in each individual. The words of Jesus revealing the power of the inner truth of his self-knowledge became better understood and recognised. With this came the insight that to follow him means to grow in the interior life, to expand the perspectives of our understanding, to deepen and clarify our consciousness.

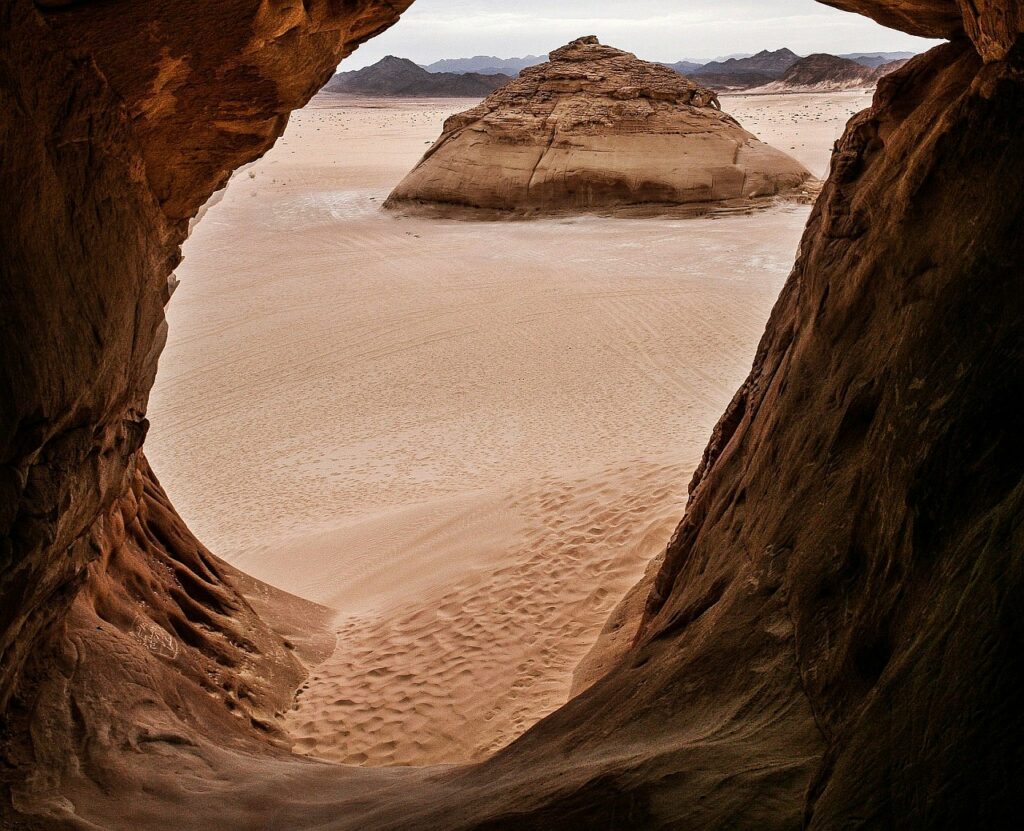

This becomes explicit not just in the lecture rooms of the early Christians but primarily in the cells and hermitages of the monastic movement spreading rapidly in the desert. The basic understanding there was to develop interiority through deep attention to oneself, while avoiding the obvious pitfall of increasing rather than transcending our egoism. Then as now the danger of contemplative life is narcissism. To avoid it we need guides, companions, discipline in practice and a robust sense of humour.

Aren’t these two of the kind of experiences which we can’t create or control but only undergo and, to some extent, perhaps, share with others whom we trust? By sharing I don’t mean we can really describe or explain them because, as soon as we try, we sound nonsensical. If you are going to speak meaningful nonsense to someone you first need to feel trust.

First, the sense of sheer wonder that the world exists and that we exist as part of it. It is wonder without the judgement that ‘I’m happy’ or ‘I am discontented’. Wonder does not even require we settle the question of why the world exists? Wonder is a pure response to what anything is in itself, without even comparing it with anything else. Childlike wonder, humbling and delightful at the same time.

Second is the conviction that everything will be OK, in the fullest sense of those two letters. Mother Julian clearly possessed it, when she said: ‘all will be well and every kind of thing will be well’. It can fill us even when appearances make us feel the exact opposite, that everything is doomed and will collapse into non-existence by tea-time.

When we play host to these experiences, we ‘feel better’ even though they don’t solve all our problems – except perhaps the big double-headed problem of despair and boredom. What makes us feel better, then, when we feel in a state of wonder and fundamental security? Whatever it is, it is like meditation – which doesn’t change external events in a magical way and at first doesn’t even numb us against the pain of uncertainty. But meditation is a quiet, gentle way of preparing us to welcome these two experiences and helping them become permanent guests and eventually co-residents in the house of being.

I trust you will forgive me if this sounds nonsense. When we think or speak about anything on the other side of language and thought we make nonsense. To make sense of it why not call the state of wonder and radical confidence ‘faith’. Belief, with which we usually confuse it, is influenced by faith; but faith itself is independent of belief. Faith is spiritual knowledge.

As we enter into the meaning of Holy Week and allow its central story to read us and show us our place in it, faith is the path we are following. We test and reset our beliefs against the experience of faith. Hiding behind faith is hope and secreted in hope is love. Like the eternal engine of God, these three are one.

From the first century of the Christian era St Ignatius of Antioch reminds every seeker today that

the beginning is faith, the end is love and the union of the two is God. Everything else follows on these and lead to perfect goodness.

The idea of sacrifice leads us deep into how human beings live and understand life. We are prepared to renounce ourselves for the sake of our children, country, cause or friends we love. Parenthood is a sacrificial offering extending over many years. But also the idea of sacrifice has shaped religious consciousness since the dawn of time. When we entered the magical way of seeing the world sacrifice became a way of influencing the higher forces and gods that controlled us. We give you this so that you will be gracious and give us what we ask.

Deeper than magic, however, sacrifice could also illuminate the deep, loving involvement of humanity and the divine powers. In Aztec mythology, Nanativatzin was the humblest of the gods. So that he could continue to shine as the life-giving sun over the earth and its inhabitants he sacrificed himself in fire.

The Eucharist fulfils this primordial religious practice and overcomes the dualism separating God and humanity and the community itself. We don’t need magic anymore and there is no fear in celebrating the great oneness. Yet, there is a great diversity in how different traditions express just how the sharing of bread and wine fuses Jesus’ offering of himself both at the Last Supper and on the Cross. None of the different styles of Eucharist with their different theologies would be celebrated, however, if it were not that doing so raised our consciousnesses of his real presence – in the fellowship of believers, in the Word and also in the ordinariness of bread and wine. In her poetic account of her mystical experience of Christ, Simone Weil included a down-to-earth eucharistic moment.

That bread truly had the taste of bread… the wine tasted of the sun and of the soil on which that city was built.

Although the Eucharist has been horribly politicised and exploited throughout history it survives in its original and spiritual freedom as a symbol of both the essential unity and the wild diversity of Christian faith. It will survive the present deconstruction of the institutions and will be re-discovered as a sacrament of the mystical Body expressing and nurturing the contemplative life.

From childhood, the gospel descriptions of the last days and hours of Jesus’ life have gripped and fascinated me as something of supreme importance and meaning. Each part of the story is part of me. As we prepare for good Friday here at Bonnevaux after a rather fun Holy Thursday celebration, it could feel like ‘well this is life’: celebration today, bad news or worse tomorrow. Does it have any meaning, this cycle of joy and misery? Or is it just about accepting what we have to? But, asking that feels like missing the point, looking for explanations where none exist.

When you can’t explain something, give statistics. Overall, the gospels give a disproportionate amount of space to describing these last hours : 30% of all the gospel texts about this 33-year-old man is given to his last two or three days. John, the deepest gospel gives 43% and 40% from Mark, the shortest and first gospel. It feels better to have measured it even though the gospels still do not give any explanation of its meaning. Why is his death so important? Why couldn’t more of his earlier life, his personality, especially his teachings, have been included and the last moments reduced?

So, although the Good Friday is so significant to me I cannot easily say why. What I was taught originally – Jesus died for us because of original sin – is the classic ‘atonement theory’. Even when I was young it didn’t convince me although I didn’t argue with it. Wittgenstein, who believed the Resurrection could only be understood by love, said that ‘whereof we cannot speak we must remain silent.’

I’ll squeeze in a few more words to explain why this response of silence can be applied to the attempt to explain the death of Jesus. First, that the details are unforgettably powerful – the last words (Father forgive them for they know not what they do; Today you will be with be in paradise (to the thief crucified beside him); I am thirsty; It is accomplished.) The scenes like carrying the cross, the soldiers casting lots, the triple denial of Peter. They all seem highly significant, inevitable, predictable, fulfilling destiny but unexplained and inexplicable.

One explanation is that the description is not just an historical narrative but a collective memory filtered through the present experience of the Risen Jesus. It is as if Jesus is telling the story himself: not to give explanations but to draw us closer to himself by our free choice.

Why tell the story at all if he had not risen?

In the Good Friday liturgy – like a global wake repeated annually – there is a reading of the Passion that stops at his burial. But the stunningly eloquent explanation is the Veneration of the Cross. People are invited to come up in silence – if they wish – and kneel before, or kiss, or simply touch the wood of the cross in silence.

When I do, I feel – perhaps like all who come forward – as if it is something definitive and authentic and I don’t need to explain it. We don’t have to justify what we love. More important than an explanation is a real encounter with a real person in a new kind of reality.

For some time death remains very hypothetical in the human panorama of life. After the brief immortality of youth, and with our first experience of losing someone we love, death seems an increasing possibility. Even when we have the inexplicable grace of accompanying someone we love to the point where ‘it is accomplished’ and they breathe their last as we hold their hand, the actual moment falls like the blade of a guillotine. As on Holy Saturday, there is a great silence, absence and bottomless emptiness.

The way a person dies can expand the portals through which the grace of death – confronting us with the barest face of truth – sweeps over us. As they hang on their cross waiting, they may be peaceful, confident, accepting and even conspicuously full of wonder at what they are seeing and being summoned to and welcomed by. We may not see it exactly as they do but we see something of it by seeing that they see it. For a moment, because of our irritating ego, we may even feel left out and forgotten as they are irresistibly drawn into what they are seeing. When they take their last breath, this shared vision appears to end, like the falling of a stage curtain at the end of a performance. We are left alone with our memory, in an ever- depleted world, as they pass beyond all the ways we have grown used to recognising them.

No more powerful words have ever been written that communicate this wonder, peace with pain and searing grief than those we heard yesterday. We see what they saw of what he was seeing through a memory passed on by those who were there and suffered changed by what they saw, but could not explain. Unlike most memories, however, it did not start to weaken from the day after and eventually fail and enter the great forgetfulness that consumes everything. The hand we are holding begins to lose its human warmth, still precious but no longer belonging to the person we loved and lost.

As she wept, she peered into the tomb.. ‘they have taken my Lord away and I do not know where they have put him’.

Holy Saturday is a state of mind: a neutral zone between what we know and do not know. It is too full of emptiness and the absence is too present and the silence is deafening.

We should not imagine anything. It is a day to make meditation the priority.

Lent begins with the tribal story of the Exodus and concludes with the myth being lived out in the person of Jesus. From today the liturgy readings focus on the events that led to the tragic climax of his downfall, death and resurrection. Today’s gospel, however, opens with an apparently mundane detail: Among those who went up to worship at the festival were some Greeks. These approached Philip, who came from Bethsaida in Galilee, and put this request to him, ‘Sir, we should like to see Jesus.’ Philip went to tell Andrew, and Andrew and Philip together went to tell Jesus. Is the point to highlight the expansion of his influence beyond the Jewish world? Or to accentuate the physical danger Jesus was in and the need for security?

At many moments in life the very uncertainty of what might be the correct interpretation sharpens our sense of reality. How often do we have a sense of uncertainty about the meaning of something or the incipient feeling of meaninglessness while we also sense that something of great significance is underway? The passing details of a loved one’s last hours of life can remain with you for the rest of yours. In important moments we pay attention to everything. including all the loose ends and unanswered questions of life.

From this point in the Lent cycle, we are swept forward in a story of inescapable intensity, drawn into a sequence of events which we have heard before. But, as with children, repetition makes them new.

Jesus has just been told that some foreigners have asked to see him. His response to this small thing is not to check his schedule. Instead, he expresses both his anxiety about the direction events are taking happen and the meaning that is now beginning to unfold and whose outcome he already knows is inevitable. His hour has come and the ultimate meaning of his young life will be fulfilled. This will happen not through success and acclaim – as we fantasise fulfilment will come to us – but through failure, pain, loss and the non-negotiability of death. He sees the necessity of this when he says that a seed has to die before it will produce a harvest.

Then, turning from his personal fate to the universal truth of the human condition he shares with us the meaning, the truth. Anyone who wants to find their life must lose it. We cannot have our cake and eat it until we have let go of the cake and our desire for it. And, if he is the way we follow, we will have to go through what he is passing through. Hard though this path seems, discipleship reveals the Father, the source, to us as it has known and lived with it since his mission began.

The exodus in this personal transition is the final break with the powers of samsara, all the alliance of illusory forces that block and delude us. What seems the end becomes transparent and we see a new beginning take shape. Everything will be made new as we free ourselves from ancient bonds and embrace the unique gift of life that makes each of us who we truly are.

It is when you say goodbye to someone that you understand what the time you spent together really meant. The ending of something allows you to see it as a whole, beginning, middle and end, and its meaning is easier to grasp. You might feel sorrow at the separation or the loss about to occur. You might sense some missed opportunities, which makes it feel you not only had a wonderful time together but also that something is incomplete and there is a residue of unrealised potential.

Maybe this is why Irish goodbyes take so long, so that people have time to reflect on all these flavours of meaning before they leave. But, probably not, they just enjoy talking, and people tend to talk more at the end because perhaps there will not be another opportunity.

Saying goodbye – as Jesus is doing in many of the passages of scripture we will read between now and Holy Week – the week of the long goodbye – impresses on us that what is past can never be repeated. We may say ‘au revoir’ or ‘hasta la vista’ or ‘see ya again soon’ – but we know that, if and when we do, we will be different people. We will recognise each other but how much will have been forgotten, discarded or have wholly faded from the pages of memory. In a sense, then, at every future reunion we will be starting again. Every farewell is a death undergone in the hope of a resurrection. But the certainty of hope – which is faith – does not mean that death does not transform and transfigure everything. Understandably, we say Let’s not leave it too long before next time.

There is a uniqueness and unrepeatability in every encounter, all relationships and contact, however brief or enduring, intimate or superficial. Uniqueness is the fingerprint of God in this life on everything in time and space.

Nicholas of Cusa was a great Christian thinker of the 15th century – cardinal and active church reformer – seen today as a transition between the medieval and the modern world. He anticipated many themes of modernity. His key insight was the ‘coincidence of opposites’ as being the ground of truth and so an especially good way of describing God. It means that God no longer needs to be thought of as separate and outside the human and natural world that He had called into being. He is here with us even when He is absent and absent, or self-concealing, when He feels most present. I learned recently that Nicholas was the first person to study plant growth and see that plants gain nourishment from the air – and that air has weight. Amazing, how much we can do in life when we are not wasting time with time-saving devices and trying to make our lives more convenient or productive.

Approaching God as the ground of being unites even the most polarised objects of consciousness in the ‘ever-present origin’ and widens the tent of consciousness which is our home in this universe. This changes even the finality of death, and so makes the daily goodbyes a little easier.

A key feature of Indian spiritual teaching is maya. It originally meant the magic power by which gods could convince humans that the unreal is real. Later it denoted the cosmic force that makes the whole phenomenal world convincingly real and enduring. This can be an attractive teaching at the mental level but a frightening one when it comes to experiencing and realising it for oneself.

It’s attractive because it seems to offer an escape route – should you ever need it or decide to risk taking it – out of the problems of this world into a real world imagined as a celestial resort wholly composed of peace and joy and selfless staff. Ramana Maharshi, the embodiment if anyone is of the wisdom of the eastern mind, is characteristically nondual about this. Yes, the world as we see and suffer it is unreal, like an image projected onto a screen or the words written on a blank page. But this concept of its unreality is a thorn used to remove a thorn. Once we have actually verified, the illusory nature of the world, as a projection of our minds dominated by ego-forces, we no longer have to reject it.

Ramana said: ‘At the level of the spiritual seeker you have got to say that the world is an illusion. There is no other way. When someone forgets that he is Brahman, who is real, permanent and omnipresent, and deludes himself into thinking that he is a body in the universe which is filled with bodies that are transitory, and labours under that delusion, you have got to remind him that the world is unreal and a delusion.’ But when you see through its illusory nature you see that God and the universe are one, the paper and the words on it are one.

Is this a problem solved? Or a path indicated? Only practice and patience can lead us gradually to see exactly what the ‘illusory nature of the world’ means. If we don’t see its meaning, we steal the idea to increase our illusory world and narrow our vision of reality. Yet experience proves that the world we think we live in as real is a projection of fears, desires and misreadings. Of course we want to escape the pain of this. But it is its illusory nature itself we should first be working on.

A practice of meditation will do this with an, at first, temporary and, eventually, unbroken effect. We can at any moment cease to worry and rage, simply by turning to the golden radiance of the kingdom within us. It is close at hand even if the path seems narrow. Change your mind, redirect the beam of your attention and place your trust in the reality that appears.

Is this a seductive call to separate us from those we love and to coldly turn our attention from a suffering world that we should rather bring engaged compassion to? First, we should come to the place where illusion and reality confront and then make the choice before we prejudge.

Recently I was on an immensely long and steep escalator at an airport. I don’t like heights but I turned around to look down. I saw a separated family regrouping themselves. As I went higher, they receded and became smaller but I saw the efforts happening in an ever-greater space. As I became more distant, I could also feel closer. Maybe dying is like this.

You cannot tell by observation when the kingdom of God will appear. You cannot say ‘look here it is or there it is’… for the kingdom is within, outside, among, between, around you. To think we can see it located anywhere except everywhere simultaneously is maya.

The Passion of Christ, like innocent suffering everywhere, suggests how wonderfully and tragically we are interwoven as human beings. It is a very crude and often cruel understanding of karma to say that when bad things happen it’s a result of our own actions. There is such a thing as chance and, although everything except Being itself has a cause, causes can be random. It’s not all about bad luck, however, there is the power of darkness arising from the action of a deluded individual, such as a global tyrant, which affects the world and whose effects last for generations.

By darkness I am thinking of ignorance, unenlightened consciousness and the incapacity to feel the feelings of others. Think of the ripple effect of the Holocaust or the pain and resentment of the Palestinian children in Gaza today or an incident of child abuse in an ordinary family that takes decades to be exposed. The interdependence of human beings is so astonishingly infinite in its nature that nothing except the principle of unity can explain it or cure us when we have been wounded by chance or darkness itself.

Yesterday I asked about the meaning of the idea that the world is illusory. It would be insulting to dismiss the suffering of a child or a torture victim as illusory and just say ‘meditate your way into oneness and everything will be alright.’ When you feel pain, it is very real and justice demands an immediate compassionate response from any human person, stranger or friend, who can offer it. The victim – it is not demeaning to be called a ‘victim’ of an earthquake or a war – has been hurt through no fault of their own and is innocent.

Innocence is the true essence of human nature and indeed of creation itself. It is what it is. When we see that the pain was inflicted through the cruelty of another person who could not understand what they were doing because they themselves were incapacitated by ignorance, we encounter the cosmic power of innocence, the goodness of creation. Even ignorance is an affliction with its own hidden causes. Jesus on the Cross asked the Father to forgive his murderers because ‘they do not know what they are doing’. He was invoking the power of truth to dispel the illusory nature of ignorance. The whole gospel is present in this, his last act on earth.

The unreal nature of the world we make up as a result of ignorance, pain and fear is tough, mean and tenacious. Rational argument rarely even dents it. All you can do is shoot down the drones it sends to attack the innocent before they do harm. We are trapped in our own crossfire: violence is the product of ignorance and history is its video loop.

Recall a time when you were locked in conflict from which there seemed no escape. Was there a moment when you or another softened and said, I’m sorry, or let’s talk or let’s start again? One word or a look is enough because love is the sole reality. Compassion, humour or forgiveness releases it from the prison of fear which is the breeding ground of the virus of illusion. Ignorance lifts like the mist. All its complicated constructs melt into air. A new world is born. At the end of his last play Shakespeare, who practiced illusion to reveal truth, understood that seeing the illusory nature of things is the reason to be cheerful:

Be cheerful, sir.

Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits, and

Are melted into air, into thin air.

And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capp’d towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it shall inherit, shall dissolve.

Shakespeare – The Tempest: Act 4 Scene 1

Sometimes you meet a young person who, although lacking life-experience, has a wisdom beyond their years. You can also meet older people, with much experience, whose development was arrested at an early stage. When you meet individuals like these you can’t help seeing what you see but, of course, always need to remember ‘judge not that ye be not judged.’ Maybe they jumped off the train for a moment and were stranded on an empty platform waiting for the next one to arrive.

The stages of human development have been closely analysed in recent times. We know that our phases of growth overlap but also have an inevitable sequence. Certain capacities, like language, social independence and emotional needs, seem to be laws of development written into the human person and follow a timeframe. Each of us develops in a unique way but we are all equal under the laws of nature. Yet there are exceptions. In some, the developmental process can get stuck and await a restart for decades. For others, well, they seem to cover decades in months. Mozart began composing at five. An eight-year-old chess player has defeated a world grandmaster.

More importantly, though, are the spiritual masters who have reached the highest level of development in this dimension. From their unique view of the panorama of reality they have given teachings that have formed lasting channels of transmission through history and many cultures. To encounter such teachers or benefit directly from their transmission through their followers is to enjoy a boost to one’s personal journey. It does not mean that the master’s experience becomes yours and they are cloned in you. But in a sense, something like this happens through a close encounter with a person of high spiritual development. Scriptures insist on the value and need to be in the presence of such individuals.

For the influence to be transmitted there needs to be peace, a faith-connection, and freedom from doubt and envy. Then something of their knowledge enters your experience, expanding your capacity for the personal realisation you must still achieve in your own way. So, it is not that you will become a spiritual prodigy just through osmosis but the ‘grace of the guru’ will accompany you on your daily rounds, protecting and supporting you in times of discouragement and doubt and helping you turn a sense of failure into wisdom.

The gospel tells a story of a feast a man was preparing but the people he invited refused his invitation. Business meetings, new possessions that distracted them or having recently got married were among the excuses they gave. The man told his people to go out and bring in the poor, the handicapped and the blind. He said – and I missed this in many re-readings I have done of the story – ‘I want my house to be full.’

I read this as an example of the humility of God which we see in the altruism of spiritual masters through history. A child once said God made people because he wanted them to enjoy the beautiful things he had made. He didn’t want to be alone A law of development is that the full empty themselves in order for the empty to be full.

Let all those who seek their own fulfilment,

Love and honour the illumined sage

(Mundaka Upanishad)

The word ‘upanishad’ means literally ‘sitting next to your teacher’ – just as you do at a meal.

There’s a simple map for the journey which every meditator is on. It helps those who are frightened to start to take the first step and encourages those who drop out to reconnect to the path. The first stage is discovering your own monkey mind and the embarrassing level of distraction that prevents you from stillness and the simple enjoyment of reality that is the fruit of attention. Giving up at the first hurdle is common but it doesn’t mean you cannot start again – as many times as you fail. You will discover the value of the selfless encouragement of meditating with others – of spiritual friendship.

The second stage is encountering the hard disc of memory. Everything, real or imagined, in our history is stored there and some of it may be repressed. Like grief, anger, fear or shame which cause suffering and control us from the unconscious. The mantra brings healing to this level of consciousness without – at the time of meditation anyway – requiring self-analysis. In fact, it is the complement of usual psychological therapy because it involves taking the attention off ourselves. This is not avoidance but detachment. Healing is the prelude to enlightenment: nothing is hidden that will not be made manifest, nor is anything secret that will not be known and come to light (Lk 8:17)

Then we touch the ego level itself, the ‘source of the I-thought’ as Ramana called it. Here we encounter a feeling of being blocked by our innate sense of separateness even as we long for the peace of union and non-duality. This brick wall has taken a long time to build and it takes time for the bricks to start falling out. As they do, we see through the wall and in God’s own time we find ourselves on the other side of it, in the Spirit. Here self-consciousness is reduced by transparency in the experience of recognition – seeing and knowing ourselves even as we know that we are seen and loved

At each of these levels, until we enter the full language of silence in the spiritual dimension, the mantra, with deepening subtlety is our faithful guide.

The important thing to remember is that as one level is reached and opens its mysteries the previous levels are not shut down. Distraction remains, though greatly reduced and at times more easily overcome. Healing continues even after the major wounds have been triaged. And the ego continues in daily life but more as a servant than as a tyrant.

This applies to other maps of human consciousness. For example, we could say we begin the journey in a pre-temporal state of oneness with all. This ‘uroboric’ mind will open to the magical with its attempt to manipulate what is now a strange, threatening world outside us. As the mind develops, we make stories – myths – to explain and manage things. Then we discover we can step back from them with rational objectivity. If we keep going, we break through into the conscious oneness of non-duality.

Wonderfully, though, all levels can stay open and be integrated with the next. Life without a sense of magic would be as algorithmically shallow as what we call ‘artificial intelligence’ but should think of as merely ‘very fast computers’. Life without the mythical imagination would lack the essential language which gives entry to the great scriptures and transcendent meaning. Rationality without these other levels contributing would be like getting the best grades at school but having no friends.

Before I became a monk I had several mini-careers including a couple of years in a merchant bank in London. It paid well and the work was quite interesting at first. I had gone there to get a break from academia and learn what really made the world go round: love or money. I had no desire to climb the corporate ladder but I liked my colleagues and found the personalities and interactions quite instructive about my other big question: what is the meaning of life and what happens to you over time?

It was this question perhaps that led me to decide to do a retreat – my first – in a monastery. I didn’t have much idea of what that meant, maybe prayer, silence, being alone, simple food. It didn’t turn out quite as I expected. When I arrived, I decided to fast as I thought that might prime me for higher spiritual experiences. What I received was a first night of intense nightmares which was something new for me and left me very shaken. One followed another and woke me up each time in a cold formless fear. No one in the monastery had taken any interest in me but I asked to speak to someone and an old kind looking monk came to see me. I described my night experience and he looked uncertain what to say; but when I mentioned I had been fasting he brightened up as if he had found the answer. ‘It was the devil,’ he confidently said. I waited for more information and he said ‘you see the devil saw you were fasting and decided to attack you because you were weak. Have a good lunch and you’ll be fine.’

My second and last night I went to my room after compline and was reading before going to bed. Suddenly there was a rapid knocking at my door. I opened it to find one of the other old monks looking very anxious and beckoning me into the corridor to follow him. I asked him what was the problem and as he shuffled ahead of me all I heard was ‘mass, mass. Theres’s no one to serve the mass. Quick!’ Before we got to the chapel the abbot appeared, apologised and rescued me from the delusions of monastic dementia.

Things rarely, if ever, turn out as we expect. The random games that the multiple universes play on us are infinite. It was a long time before I entered another monastery to learn from the teaching and personal example of the wisest and sanest person I have known before or since. Wisdom, goodness, personal sanity and who we learn from make all the difference to our life. But even then things never turn out as you expect.

We are God’s work of art, created in Christ Jesus to live the good life as from the beginning he had meant us to live it.

Ephesians 2:10

So writes St Paul in the second reading of today’s mass (Ephesians 2:1-10). It strikes me like a chord or melody of Bach, who I could listen to all day, that suddenly emerges from his music, transcending everything that has prepared for it and, soaring high above all contradiction with an effortless joy and sapphire blue simplicity. Merely to argue with it would feel like the perverse jealousy of the ego when it is confronted by the self.

The idea that we are actually created is difficult to grasp. It’s beyond our backward view of things. Whatever knows itself has the feeling from the dawn of consciousness that it has existed for ever. Maybe this was Lucifer’s mistake, a deceptive perspective. In the same letter Paul addresses the dilemma like this: ‘he chose us in him before the foundation of the world, that we should be holy and without blemish before him in love’.

You can’t argue with the ground of being. You can never undermine it. You can only try to accept your degree of self-knowledge in humility. However uncomfortably to our independent spirit, it reveals that we are accepted, chosen, known, before we emerge into the world of space and time. Our meaning in this emergence is to learn to enjoy the goodness of life by realising we are a creation, not self-made and therefore not self-sustaining, but a spontaneous emanation of divine beauty. But enough of this, or we will be drawn into the maze of the gnostics instead of simply walking the labyrinth of our lives in the faith of being unfinished works. We are God’s work of art still incomplete; but, as God doesn’t do bad art, so we must be uniquely beautiful.

Little dramas of human relationship illustrate this. When a friendship is interrupted for no obvious reason, days and months pile up a seemingly endless absence separating us. It is easy to imagine rejection, something misunderstood, a failure or fault on our part, guilt for an unknown fault. The more we imagine the worst reason, the harder it is to reach out towards the other person – even with the life-giving words ‘how are you?’ Life goes on but the part of us that was given into the friendship is lost, part of life’s collateral damage. Then the absent one is there again by chance, unexpectedly. Before either of you know it you are conversing, catching up and coming to understand what happened. No blame. No fault. Just trust mistakenly placed in fearful thoughts.

Read today’s gospel (John 3:14-21) in the light of this. God loved the world so much that… Where you read ‘believe’ put ‘have faith in’ and see how it changes the landscape.

Everything depends on perception: how we see things and the response we have to what we see (or think we see). Theoretically, we value objectivity and detachment and like to feel we have these qualities but, even in the rigours of the scientific method, what is objective to me may seem sheer prejudice or stupidity to you and even, after the event, mistaken to me. How can we ever be sure that what we perceive is real and that our way of seeing has value. Perception is all-important but perspective shapes perception even without our knowing it. Perspective is constructed of all our cultural, educational and personal influences. Our crisis is that the perspective we took for granted is collapsing.

The era we are in – and feeling our way through – is in a crisis of perception caused by the shifting of fundamental perspectives that are shifting just as tectonic plates deep below the surface of the earth move imperceptibly until they produce a devastating earthquake. In such times, feeling like sheep without a shepherd or like a car running downhill whose brakes have failed, we dash from pillar to post trying new solutions and doubling back on ourselves when we reach another dead end. Life is no longer perceived as an amazing revelation of the mystery of creation. It feels like a maze and we like mice caught in it desperately trying to find the way out.

However, there is an all-important distinction between a maze and a labyrinth.

A simple kind spiral-labyrinth is among the most ancient designs painted by human hands on the walls of magical-mythical caves up to 40,000 years ago. In classical times and later in the Middle Ages the more sophisticated labyrinth, such as we can still see on the floor of Chartres Cathedral, looks uncannily like the two hemispheres of the brain or, to some, the intestinal tract. It is a spiritual practice to walk it as it calls to the conscious mind what is unfolding or blocked in the unconscious. To the meditator, it is a symbol of their daily inner journey. It requires faith and perseverance to do the labyrinth, following one narrow path, one measured step at a time, which we enter through a single entrance which is also the single exit once the journey has been completed. The labyrinth is a unicursal pilgrimage which tests our faith because it can it seem to lead away from the centre it is leading to. God doesn’t write straight with crooked lines. He draws curving lines that we try to improve on by straightening them out.

While the labyrinth is a pilgrimage that we learn to follow, a maze is a problem to solve, a puzzle to master. Mazes have multiple entrances and exits. The goal is to just to get out once you have got lost and getting lost is the thrill – or the horror of it. There are also frequent dead-ends which force you to the retrace your steps and face the fear of never getting out. A maze, then, is a corrupted labyrinth and works as a metaphor for what many feel modern life has become. Whoever designed the first maze was expressing a disgust at the meaninglessness of life in the same way that makers of horror movies are tapping into those fears of our inner darkness that build up for explosion behind the mask of false optimism.

Meditation converts the maze into a labyrinth. As it does so, life once again becomes truly amazing.

The students and some of the faculty of the WCCM Academy are meeting together in Bonnevaux this week. Although most of our previous encounters have been online, an extraordinarily warm, trusting and energised bond has developed among all. Vladimir Volrab, the Director of the Academy, has helped create this unique environment for a contemplative learning group, with skill and sensitivity. He manages the connections between participants from different parts of the world in class and other times with personalised care which allows each to grow interiorly but also see each other’s growth. As St Benedict understood, in any community practical things should be done smoothly and ‘in good order’. Then, all involved need not become sad. Few things make us sad more quickly than messy organisation. Meeting with the students to discuss their reflections on the course on Jesus (‘Who do You Say I Am?’) that I taught last term, I was moved and inspired by their joy and the wisdom evident in their eagerness to share.

I had asked them to share their personal experience of the stages of the journey of their relationship with Jesus. How difficult it is to put this into words in an abstract way – as we do when we reduce experience to ideas or formulas. It is like the challenge of explaining to people who don’t meditate why you do. Our relationship with Jesus – even this phrase can be discomforting – can best be expressed by a simple but transparent telling of the story of how it happened and how it continues to is evolve.

Most referred to their early childhood, whether in a religious environment or not. Religion in early life, even when very flawed, at least gives us a language for the future. Where there has been no such formation, reflecting on our raw experience will develop a language of its own which can later engage with the language of tradition. But the strongest formative influence in the development of an ongoing encounter with Jesus at an authentic level was people. It was through the individuals who influenced them at different times of their life – people of all kinds and ages from a childhood friend with a terminal illness to an old person who compensated for something missing in their lives. In these relationships faith could be felt to be alive without any attempt to persuade or manipulate. Simply by their presence and personality, their example of living embodied it.

This can be put even more simply. It was through certain individuals that the members of our group here first felt unconditional love. A love that was characterised by tenderness and concern, but also marked by great personal detachment. What releases our capacity for spiritual growth, it seems to me as I listen to these stories shared with such transparent trust, is discovering that we can be loved with a perfect love by other human beings. These are otherwise ordinary people whom we relate to in an extraordinary way. They have become channels of the love we yearn for and may call ‘God’. Then we see how God can be, is, fully human and indeed was so in an individual we dare to call Jesus who is the grace of the great encounters of our lives and whom we can meet even when we don’t know it.

Throughout his teaching Jesus specifically tells his listeners to abandon their habitual state of anxiety. He urges them to ‘set your troubled hearts at rest and abandon your fears.’ In the same vein, St Paul says to his fledgling Christian communities that the guide and compass of their whole life of feeling and action should be the peace of God which is ‘beyond understanding’, rather than ceaseless conflict and dejection. We should not and need not live oppressed by fear and stress, anxiety, dread or panic.

Living in an age of anxiety reaching levels that are linked to chronic physical and mental illness, depression, obsessiveness and inability to concentrate, insomnia and digestive problems, we might listen to Jesus, thank him for the nice words and think ‘well that’s easy for you to say.’

In fact, he is not giving advice but an authoritative teaching and a challenge to make a journey that will seem long and hard. He indicates how this can be achieved: by embracing the gift of peace that he promises to leave behind when he has gone. A peace ‘such as the world cannot give’ – the short-lived reduction of stress created by self-distraction and over-consumption – but his own peace. But how can you give peace to another person that is more than a comforting arm around the shoulder? He seems to be speaking about a direct and targeted transmission, face to face, heart to heart, of a boundlessly renewable energy.

To receive this transmission we have nothing else to do except open ourselves to it and trust it before it appears. Sometimes, however, fear locks us into a paralysed, self-harming pessimism which we cannot escape. We end up craving consolation rather than desiring transformation. No wonder the injunction to transcend the grip of fear is the first step of the spiritual journey in all traditions. The ‘fear of God’ as it is translated from the Bible doesn’t mean fear in the sense of expecting punishment. The fear of God – awe, wonder and peace –is the cure for the fear that blocks us from making the human journey.

The Sufi poet Attar wrote an allegory of this journey to God called the ‘Conference of Birds’. Every kind of bird comes to a meeting and decide to set out across the seven valleys to find the king, called the Simurgh. The word ‘simurgh’ means literally ‘thirty birds’. As the time of departure approaches most find excuses not to go. Of those who set out many turn back. In the end only thirty bedraggled birds arrive at the king’s palace having spent most of their lives on the journey. They are met by a servant who tells them they are unworthy to enter and to go home. But when they insist, he tells them that, even should they enter, the glory of the king will reduce them to nothing. They reply that a moth desires to be one with the flame it is attracted to. The thirty birds enter the presence of the Simurgh and seeing him they realise that he is themselves.

They see the Simurgh – at themselves they stare

And see a second Simurgh standing there

They look at both and see the two are one.

The peace beyond understanding and the end of fear is the disappearance of duality.

Ramadan is the Muslim equivalent of Lent. Observant Muslims fast each day until sunset as they mark the month when the Qu’ran began to be revealed to the prophet Mohammed. The actual beginning of Ramadan depends upon the first sighting of the new crescent moon which this year took place last Sunday in Saudi Arabia.

While the fast from food and drink begins, the orgiastic feast of violence in Gaza continues unabated. The ceasefire that civilised nations have been calling for has not been agreed. Humanitarian corridors have not been created to permit aid to reach those in extreme suffering. Children, non-combatant women and old men continue to be killed and the numbers of newly mentally and physically mutilated who are entering a life of extreme hardship grows every day. While the religious fasting begins, the UN has warned that a famine in northern Gaza is almost unavoidable.

Aren’t human beings interesting? There is a story from Auschwitz about a group of rabbis who were discussing whether God had broken his covenant with His chosen people by permitting the Shoah. Exhausted and hungry at the end of the day, they convened a court in their freezing hut to put God on trial. It did not take long to find Him guilty. He had clearly abandoned His people. Then the presiding rabbi concluded: ‘we will now say the night prayer and go to sleep.’ I asked an old rabbi friend of mine once whether he thought God had favourites. He said that as a young man he had no doubt: it was the Jews. Later he came to believe that God had no favourites but loved all equally always. Now, he said, he felt God’s favourites did exist: they are the ‘anawim’, the most poor, abandoned, rejected of humanity whatever their faith or ethnicity.

It seems that the practice of religious faith is resilient to a point of sublime absurdity. Perhaps, as the conditions of human decency collapse around us and the spirit of religion is rejected, the outward signs of faith assume a new, paradoxical significance, as the last hope that human beings can be rehabilitated after they have dehumanised themselves. These religious practices are then no longer superficial or routine or merely tribal signs of belonging; they have acquired a radiance, even a paradoxical kind of glory because the mystery itself, beyond all signs and words, is exposed through them when humanity is in its most desperate state.

We might mock this. Or we might glimpse what shone through in that hut in Auschwitz or in Ramadan in the bombed hospitals in Gaza today. It is something we need not even try to name. Yet, if we see and recognise it, we are compelled to dive into the deepest silence where solidarity with the suffering of humanity reveals the core reality of the resilient oneness, even of oppressor and victim.

It is often said that spiritual teachings in all traditions urge us to develop an indifferent attitude to happiness or unhappiness. This reflects the teaching of Jesus that the sun of divine benevolence shines equally on good and bad alike. Does this mean we should aim to have no preference? Or, more realistically, that we should accept the rough and the smooth and take the rough graciously without complaint. Buddhist teachings emphasise the danger of clinging

to any one side of experience because we then bounce between aversion and possessiveness. Yet Buddhists are not indifferent either. They believe in reducing suffering and in a state beyond it which we should aspire to. Similarly, the Gospel teaches us to ‘consider that the sufferings of the present time are not worth comparing with the glory to be revealed in us’ (Romans 8:18).

The problem in assuming that we should be equally happy with suffering or joy is that it is unrealistic. It is not true to human nature or to the meaning of suffering. It is not detachment, more like estrangement. The true wisdom of the spiritual traditions is to avoid what suffering we can avoid and graciously accept what we cannot with the confidence that suffering is not meaningless. Thus we are brought closer to the source of joy within ourselves that is reflected

in all natural cycles.

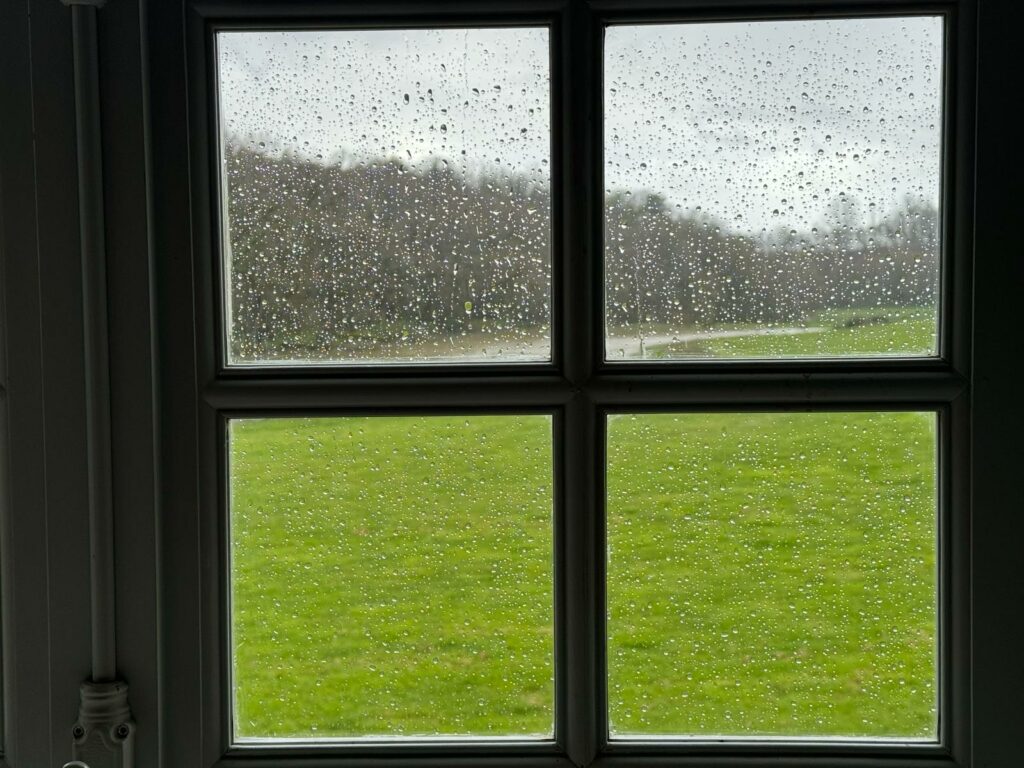

One test of this is the arrival of the entrancing season of Spring in the Northern hemisphere. I can see it happening today as I look out of the window as I write this at Bonnevaux. Senses awake, forgotten scents, new colours and textures return, joy-filled daffodils and the green wash you can hardly see in the bare trees emerging from their seasonal death. We have had a grey, wet winter with several of the extreme variations that are characteristic effects of climate change everywhere. Nevertheless, thank God and His manifestation in the beauty of the world, that the timed wheel of the seasons is still turning.

Another simple test is our preference for life over death even when, like Jesus in Gethsemane, we accept the painful destiny of death as part of life. The love of life transforms this destiny. Because it is so deeply rooted, it touches in us the core of eternal life free from the cycle of death and rebirth within which we grow but which we also transcend.

Looking down the Bonnevaux valley today, I can authoritatively say that Spring is still spring. Few are they who would say they don’t prefer it to winter. We are time travellers passing through a cycle of spirals, measured by the sun and moon, towards the solitary source where all are at home. Through each revolution and repetition we come deeper into resurrection, the union of opposites where what we once just glimpsed is proved real.

Those who realise Brahman live in joy

And go beyond death. Indeed

They go beyond death.

OM shanti shanti shanti

(Aitareya Upanishad)

Speaking of preferences… Do you prefer to meditate alone or with others? And why?

Some people find meditating with others to be beneficial because the presence of others helps them to strengthen the basic disciplines of the practice, like regularity, punctuality, physical stillness and meditating for the full time. If you are part of a group, say on a retreat or in a community meditating at regular times during the day, when you see the time or hear the bell calling, some additional force kicks in to pull you to the meditation space. You feel physically and emotionally part of something and your presence with the others in the group completes it. You may even feel that it is when people meditate in each other’s presence that ‘meditation is creating community’. In physical ways during the meditation, the discipline of stillness, of body and mind, work together. Controlling your coughing, throat clearing, sneezing and scratching becomes a generous part of your contribution to the peaceful stillness of all the others around you.

On the other hand…

I prefer meditating alone because it is a solitary practice. I can’t meditate for you, nor can you for me. Yes, we can meditate together but then there are even more distractions. What if I am next to someone with an itchy skin complaint, a noisy tummy or a persistent cough or who shifts their sitting posture every few minutes? I could remind myself of a zen story that puts the blame on me. The anger I feel is already inside me, etc. I found some truth in this when I realised that the irritation arises mostly when you yourself are mentally distracted; but when your mind is calm, external distractions can pass without hooking your negativity. Nevertheless, you need some time to get to that calm spirit of attention and if you are irritated and distracted by your neighbour from the beginning you may not reach anywhere near that restful green valley. ‘I’m surrounded by noise and other people all day. Meditation is my time for solitude, to get away to my cave in the Himalayas, the cave of my heart.’ Meditation as someone once innocently said, is my ‘me time’.

How do we balance the advantages and disadvantages of each way of meditating? Is it just a matter of temperament? We could also ask if there is an either-or-ness about meditating alone or with others.

When I meditate alone I enter the particular space-time of solitude which is the cure for loneliness. Solitude is the discovery, recognition and embrace of our eternal uniqueness. This is far from the ego’s rabid defence of its individuality. In my uniqueness ego has been dethroned and I am capable of relationship, communion, of a depth and meaning the ego has no knowledge of. The peace in solitude is an emanation of my participation in the great shalom of the cosmos, the oneness in which fear, desire and conflict dissolve. Solitude therefore, as Keats said in his poem to her, can be shared:

…it sure must be,

Almost the highest bliss of human-kind,

When to thy haunts two kindred spirits flee.

Meditating alone I am in communion with others. Meditating with others I am part of the making of communion. Seeing that truth, rage at a neighbour’s fidgetiness or rumbling stomach can be harnessed and turned into patience and compassion for someone who is already part of me.

Today’s gospel (John 2:13-25) describes Jesus purifying the Temple in Jerusalem. Outraged by the commercialisation of this sacred but also politicised space, seeing the animals being sold for sacrifice and moneychangers exploiting foreign visitors during the busy time of Passover, he reacted with anger. He made a whip of cords and drove the animal merchants out; and then turned the money-changers’ tables over scattering their coins. His reason was clear: ‘You must not turn my father’s house into a market.’

Catholic pilgrimage sites, like Lourdes, have built their economies around pilgrims but, perhaps remembering this passage, the sacred zones themselves are commerce-free. Last month the Extinction Rebellion activists dressed in business attire occupied insurance companies in the City of London which, they claimed were complicit in climate chaos by insuring companies involved in environmental damag. The Occupy Movement protesting social and economic inequality disrupted Wall Street. Greta leads school-children strikes. In all these cases, as no doubt in the Temple, once the disruption is over, things return to normal and the money-changers haggle to recover their scattered coins. Protests like these don’t bring radical, lasting change; but they do raise and sustain awareness of injustice and challenge stay-at homes like most of us to take sides, thus helping us feel less helpless and hopeless.

They are easily dismissed as emotional, ineffective responses. But when people feel helpless what matters most to them is to enjoy freedom of self-expression – precisely what is being crushed in the rise of repressive totalitarianism in countries like Russia, China and Iran. We need protests that don’t seem to achieve anything but say something nonetheless. Yet anger without depth can lead nowhere or worse to bitterness and despair.

In the gospel Jesus explains his behaviour in the Temple in the deepest mystical terms: identifying the Temple with his own resurrected form of embodiment.

The wonderful film Jesus of Montreal, shows a contemporary Jesus-figure mirroring the events leading to his death and resurrection. He leads a motley group of actors among whom, in one scene, the Mary Magdalene figure is auditioning, lightly clad, for a TV beer commercial. Jesus is present in the studio and witnesses her mocking, degradation and humiliation by the producer. Jesus stands up and silently, calmly walks round pushing over the expensive cameras and lighting. This leads to his trial and eventual death.

We are obsessed with objectives, outcomes, measurables for all we do, oblivious to the wisdom of the Bhagavad Gita on work: You have a right to perform your prescribed duties, but you are not entitled to the fruits of your actions. Never consider yourself to be the cause of the results of your activities, nor be attached to inaction. (BG 2:47).

Anytime, anywhere in the world when anyone sits to meditate, they are making the perfect protest against the illusion that underlies injustice. Each meditation witnesses to truth and kindness and bring them closer to being realised.

The thousands of people who dared to go to Alexei Navalny’s funeral in Moscow last week were risking a lot, not least their physical freedom. Why do so for a such a gesture? In making it they declared that they could see through the lie under which the Russian state is forcing its citizens to live. It does not demand that people believe the lie but only that they deny that it is a lie and join the pretence it is the truth. Making people live like this – and religion and most social institutions, including families, have a history of doing the same – is to destroy their soul in return for acceptance and security. But what’s the point if we gain everything we want at the cost of our true self?

The mourners were also testifying, courageously in such a lie-saturated society, that only ‘truth will set you free’ (Jn 8:31).

Truth is suppressed as soon as we start thinking of it as an answer, an explanation or a dogma. The Greek word for truth is ‘alethia’ which means literally ‘not being concealed’ or ‘unhiddeness’. It is interesting that it should be expressed in this apparently negative (apophatic) way rather than being a straightforward definition. But truth is never a fixed thing or at least not for long. The experience of truth is when we see and feel the continuous clearing away of falsehood or illusion. We could say it is revealed as the pure ‘isness’ of things – or people – their authenticity and real presence.

This why we feel the truth in a person’s being as well as in what they say; but most fully we see the truth in what they do. The theologian, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, struggled against the Nazi lie until he finally joined the resistance to Hitler which he paid for with his life. It led him to see, what the rest of us learn from daily experience, that truth is always the right thing to do. It is in action not just words that truth is revealed.

It is in doing the right thing that we rise above the fears and desires of the isolated and self-centred ego consciousness. We do this when we do meditation, when we are not daydreaming:

So cut through the strap and the thong and the rope. Unbolt the doors of sleep and awake (Dhammapada 26)

This is how truth sets us free and shows us that freedom, too, is not what we usually think. It is a relationship between two people in which we are free for the other. Bonhoeffer said, ‘only in relationship with the other am I free.’ This is why meditation brings people together in unity and why the mourners in Moscow last Friday were a sign of the new Russia waiting to be set free.

Navalny, like Bonhoeffer, showed supreme detachment to make his sacrifice. Detachment – which is discipline – is necessary for us to know the truth which sets us free. At the heart of this mystery of being is a state of non-clinging and even non-action. Again, the Dhammapada describes it beautifully:

Like a mustard seed on the point of a needle,

Like a drop of water on the leaf of a lotus flower,

We do not cling.

You always bring things back to meditation, someone once said. I don’t apologise for it, as I feel without the level of experience that meditation opens all the rest we say risks being just theory – or habit or worse. The ever-fresh challenge is to come back to it differently, like a musician to the repertoire they love. I was once in a conversation with Yehudi Menuhin and was about to ask him how he felt about always coming back to Bach and Beethoven, pillars of his art; but thankfully before I could ask such a naïve question, I understood the answer. (It would have been like asking ‘why did you stay married to one woman for fifty-two years?) He did say on another occasion that time gives a dimension to relationship that no other dimension of reality can do. I saw the truth of what he said but didn’t ask why. I suppose it involves the heightening sense of mortality which time bestows on us.

Speaking about meditation, I also come back to the important fact, on which the future of the world may depend, that children take to meditation like ducks to water and enjoy it pure and simple, whereas their elders see it as a superhuman challenge beyond their capacity and tend to dilute it – or deny it. The only real teacher is experience; so there is little point in arguing about it with someone who pre-judges the experience.

There are various paths to meditation practice. Genuine practitioners should not compete and, if faithful to their main practice, will enjoy and benefit each other. All that matters is: does it open us to the state of contemplation – silence, stillness, simplicity – the simple enjoyment of the truth – beyond thought, word and imagination. Let’s take the mantra and do a sketch-map of how it leads us there.

First, we say it and discover the chaotic indiscipline of our minds, our lack of attention. It is like someone going for a mountain walk after weeks of convalescence. It’s hard-going and you shouldn’t overdo it. But practice, returning to the mantra, strengthens the all-important muscle of attention. Soon, less effort is needed even though the distractions are still present, sometimes overwhelmingly depending on our experience at the time and generally how we live. We could all meditate more deeply and enjoyably if we made a few changes in our lifestyle. Then you begin to sound the mantra and discover the natural harmony which prevails at the deeper levels of yourself. We are getting to know these new levels consciously for the first time. Tasting the peace and joy already within us promises the wonder of going beyond limits (aka eternal life). Whether we name it or not we are beginning to know God. If you are on a Christian journey, you will recognise Him. The third stage is not final because it is takes us over the boundary into the spirit. The mantra shows its purpose as it becomes more subtle and finer and we listen to it, lightly detaching our attention from distraction and the self-reflection which is the root of the illusory self.

When you are lost and your GPS battery is dead, you fall back to the old human practice of asking a passerby the way. You know quickly if they will be of help. The best is, they tell you in a way you can remember. Worse is if, like the Irish, they give interesting but too detailed directions. Worst are those who cannot say ‘I don’t know’ and make up an answer. Even in the worst scenario, getting lost might awaken our inner sense of direction. We are never actually lost.

Psychologically, we all need to aspire to a healthy individuality. One important way to fulfil this is to be close to healthy individuals who have a healing and balancing effect upon us, allowing us in our own way to be of help to others. But healthy individuals who have this effect are few and far between especially in a society as disturbed as ours.

Just having this aspiration is a good beginning and it develops by being aware that we have room for improvement – controlling our negative feelings, developing our capacity to give attention to others and so on. It’s consoling to know that, although we may not be very healthy individuals, does not mean we are all bad. Far from it. No one is perfect. Accepting our shortcomings, however, means we refuse to be dragged into self-rejection or self-hatred. For this, we need to feel the love and acceptance and unconditional forgiveness of those who know about or have even suffered from our faults. Community and family – if there are sufficiently healthy individuals in them – provide the love that allows us to be as loving as we can be at the stage of wholeness we have reached. Jesus insisted he did not come to condemn but to heal and why a true church does not exclude sinners but welcomes them.

What does healthy individuality mean? The best definition is a human being who exudes it.

Every human being is affected by an inner conflict between two aspects of their individuality which are striving, throughout life, to be integrated: like a double image trying hard to be set as one. One aspect of our individuality interprets everything from the outside, with itself as the illusory centre of everything. If we get stuck in this, we pursue power and control at any cost over others and become cruel (to others or ourselves) and disassociated from reality. A great deal of energy, which maybe is not available in this realm of time and space, is needed to pull us out of this extreme self-orbit. But even the majority, the less tragically divided and isolated individual, remains unhappy and creates unhappiness. However, they are still open to the ever-present grace of healing. Most of us even while making progress oscillate between the two states.